As hospital expenses rise, charity care spending falls

By Alex Kacik / November 27, 2023

As nonprofit hospitals’ expenses rose during the COVID-19 pandemic, they provided proportionally less free or discounted care, also known as charity care. But the trend may shift as Medicaid beneficiaries lose coverage and as lawmakers ramp up pressure on providers.

Nonprofit hospitals’ median operating costs jumped roughly 20% from 2020 to 2022, according to a Modern Healthcare analysis of data from 255 health systems—comprising most U.S. nonprofit acute-care and specialty hospitals—compiled by Investortools-owned Merritt Research Services. The increase may explain, in part, why health systems’ median charity care as a percentage of operating expenses declined from 1.21% to 0.99% over that time period.

“When your purse is tight, you tighten the string,” said Ge Bai, an accounting and health policy professor at Johns Hopkins University, who studies hospitals’ charity care spending. “Hospitals had to squeeze their charity care spending to maintain financial viability.”

Expanded Medicaid coverage—and the corresponding lack of need for discounted or free care—could have been another contributing factor to declining relative charity care spending. Medicaid enrollment grew by more than 21 million from February 2020 through 2022, according to KFF data. The federal government also allowed many Medicaid beneficiaries to remain enrolled during the public health emergency, even when their income should have excluded them from the program.

"The necessity to provide higher relative levels of charitable care has been suppressed by economic and political conditions,” said Richard Ciccarone, president emeritus of Merritt. “A true test of relative charity care spending levels will come later if unemployment goes up, uninsured patients rise, and the expanded Medicaid program is no longer reflected in the numbers.”

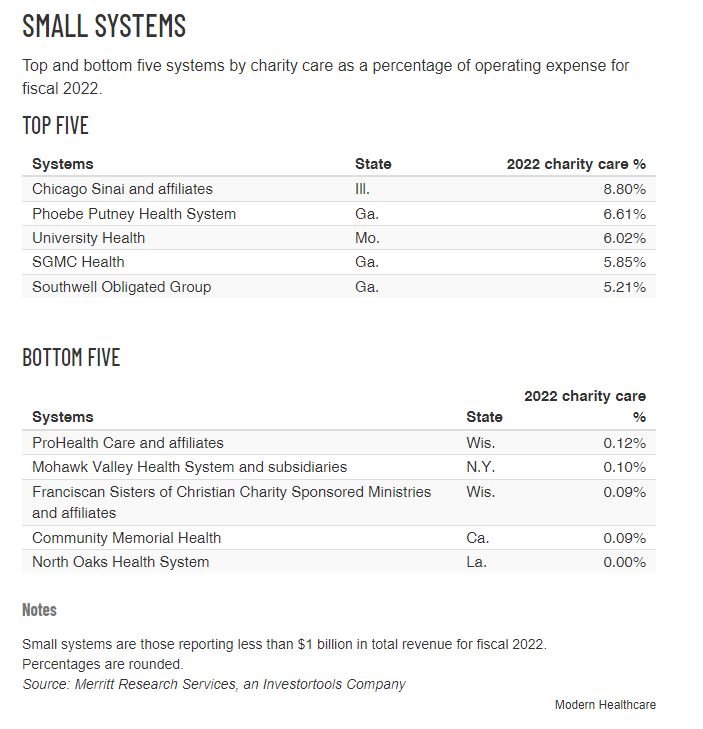

Modern Healthcare analyzed Merritt's data on operating expenses, operating margin and charity care for 255 health systems that reported all three for fiscal 2020, 2021 and 2022. In addition, Merritt provided Modern Healthcare with information regarding the five health systems in each revenue category that spent the most and least on charity care in fiscal 2022, according to its data. Each of the health systems in Modern Healthcare’s analysis had at least $10 million in debt.

In response to Modern Healthcare's and Merritt's charity care data analysis, the American Hospital Association pointed to the significant increase in hospital operating expenses in 2022. Melinda Hatton, general counsel and secretary at the association, said in a statement that charity care is only one aspect of hospitals' community benefit, including community programs and filling government program reimbursement shortfalls.

Springfield, Massachusetts-based Baystate Health and Northern California-based Stanford Health Care had the lowest relative charity care spending among health systems with more than $3 billion in annual revenue, according to the Merritt data. The health systems dedicated 0.16% and 0.24%, respectively, of their operating expenses to charity care, compared with the fiscal 2022 median of 1.01% for systems of that size. Baystate did not respond to requests for comment.

A Stanford spokesperson said in a statement that the state average for charity care is less than 1% because of Medicaid expansion and California’s extensive safety net for low-income patients, including 172 federally qualified health centers.

“Our organization is dedicated to providing generous charity care,” the statement said. Stanford provided $714 million in community benefits, which include charity care, amounting to nearly 12% of its operating expenses in fiscal 2022, according to the statement.

Health systems have seen unpaid medical bills and charity care spending levels rise this year as states resumed Medicaid eligibility checks in April, according to data from the consultancy Kaufman Hall. As of mid-November, more than 10 million people have lost Medicaid coverage this year.

West Reading, Pennsylvania-based Tower Health, which was among the lowest relative charity care spenders for systems reporting between $1 billion and $3 billion in revenue in fiscal 2022, said it recently updated its practices to help patients qualify. For fiscal 2023, Tower's charity care totaled more than $40.4 million, a spokesperson said in a statement. According to Merritt data, Tower spent $2 million on charity care in fiscal 2022.

Scrutiny ramps up

Charity care spending relative to nonprofit health systems' overall expenses has remained stagnant or dropped over the past decade, Modern Healthcare analyses show.

Nonprofit hospitals have failed to keep up with their obligations to the communities they serve over the past decade, said Vivian Ho, a health economics professor at Rice University who studies hospital charity care spending.

The trend has prompted scrutiny from agencies and lawmakers regarding whether nonprofit hospitals are earning their tax-exempt status.

“Hospitals have been dinged for not sufficiently pursuing charity care for financially eligible patients and taking them to collections too soon,” said Katherine Hempstead, a senior policy adviser at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a research institution. “It will be interesting to see as they are under more pressure for that, if they might increase charity care spending."

On Nov. 20, Vancouver, Washington-based PeaceHealth agreed to pay up to $13.4 million to 15,000 low-income patients following an investigation from Washington Attorney General Bob Ferguson (D) that found the nonprofit health system billed patients who likely qualified for financial assistance. In addition, Ferguson filed a lawsuit in February 2022, the outcome of which is pending, against Renton, Washington-based Providence, alleging the nonprofit health system failed to notify patients who qualified for financial aid. Meanwhile, Washington enacted a bill in 2022 that established mandatory discounts for patients with incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level.

In July, Oregon Gov. Tina Kotek (D) signed a bill that looks to increase access to charity care by requiring hospitals to proactively screen patients and streamline the signup process. A similar law went into effect in Minnesota in November.

Historically, state and federal policymakers have been reluctant to address charity care and community benefit spending, in part because there are so many variables affecting hospitals. Charity care spending levels vary based on a hospital's patient and payer mix and their surrounding community infrastructure. For instance, most hospitals that reported the highest levels of relative charity care spending were located in states that had not expanded Medicaid, according to the Merritt data.

Another Oregon law, enacted in 2020, tries to address some of the variables by setting charity care spending minimums on a sliding scale, based on Oregon nonprofit hospitals’ annual income, community benefit spending and the needs of their surrounding communities. Failing to reach those thresholds could result in financial penalties.

Strong hospital lobbying groups have also deterred stricter oversight of nonprofit hospitals, industry observers said. But federal congressional members are revisiting the conversation. Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), Raphael Warnock (D-Ga.), Dr. Bill Cassidy (R-La.) and Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) sent a letter in August to the Internal Revenue Service pushing, in part, for required standardized community benefit reporting, including charity care spending.

The senators cited a recent KFF report that found nonprofit hospitals received $28 billion in taxpayer subsidies in 2020 but provided $16 billion in charity care.

“There’s certainly a growing contingent within Congress saying the Internal Revenue Services needs to take a more active role,” said Gary Young, director of the Center for Health Policy and Healthcare Research at Northeastern University, who studies hospital charity care spending.

Declining rates of relative charity care spending raises the question of whether hospitals should shift more resources to other community benefits, such as building housing, Young added.

“If hospitals are not providing a lot of charity care, should they act more like the health department? That requires a major shift in mindset and resources,” he said. “Hospitals historically have not been resourced in such ways.”