Health Cost and Affordability Policy Issues and Trends to Watch in 2024

By Krutika Amin, Emma Wager, Zachary Levinson, Juliette Cubanski and Cynthia Cox / January 24, 2024

While issues of health care costs and affordability may not be at the forefront of this year’s election, they remain a major concern among the public. Health spending in the United States is projected to grow by 5% between 2023 and 2024, to a total of $4.9 billion. Here are key health costs and affordability policy issues and trends to watch in 2024.

Will policymakers pass site-neutral payment reforms?

Payments for outpatient services frequently vary depending on the type of setting where they’re provided. For example, reimbursement rates are often higher for a given service when provided in a hospital outpatient department versus a freestanding physician office, even though in many of these circumstances care may be safe and appropriate in either setting. Policymakers and payers have expressed interest in aligning payments across care settings through “site-neutral payment reforms.” Through legislation and rulemaking, Medicare has aligned payments for office visits across freestanding physician offices and off-campus hospital outpatient departments—which often resemble physician offices—as well as for other services for relatively new off-campus facilities. The U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill in December 2023 (HR 5378) that would align Medicare payments for drugs administered in off-campus hospital outpatient departments and freestanding physician offices, which the CBO estimates would save $3.7 billion over 10 years. Other proposals, such as aligning payments for both on- and off-campus hospital outpatient departments with payments for ambulatory surgical centers or physician offices for certain services, could lead to much larger savings. Policymakers have also explored reforms intended to address outpatient facility fees—which are on top of professional fees for a given service and can add substantially to the total bill—charged by hospitals and other institutional providers in commercial markets. In addition to directly lowering costs for payers and individuals, site-neutral payment reform could reduce the incentive for hospitals to buy up physician practices, a practice which has been associated with higher commercial prices. Nonetheless, hospitals and other opponents have argued that there are differences in the patients that hospitals care for, the services they provide, and their cost structure that justify higher payment rates.

Will price transparency requirements drive down costs?

Federal price transparency requirements exist to allow consumers to compare prices across hospitals and providers. Health plans and employers may also be able to use some of the price transparency data to negotiate lower rates. There is bipartisan interest in price transparency and recently the U.S. House passed a bill (HR 5378) codifying existing price transparency regulations and extending the requirements to diagnostic labs, imaging services, and surgical centers. However, the Congressional Budget Office expects price transparency to have very little impact on health sector prices. State-level studies suggest price transparency can result in unintended consequences if it results in competitors demanding higher prices. Additionally, few consumers use these tools to shop for care, and those who do try to price-shop may find that timely or convenient alternatives are not available. For price transparency to make a meaningful difference in costs for consumers, targeted approaches with a more limited set of services that consumers truly shop for may be most effective. Price transparency is a largely bipartisan issue, so federal solutions to these issues are not impossible in 2024.

How will prescription drug pricing policies affect health spending and affordability?

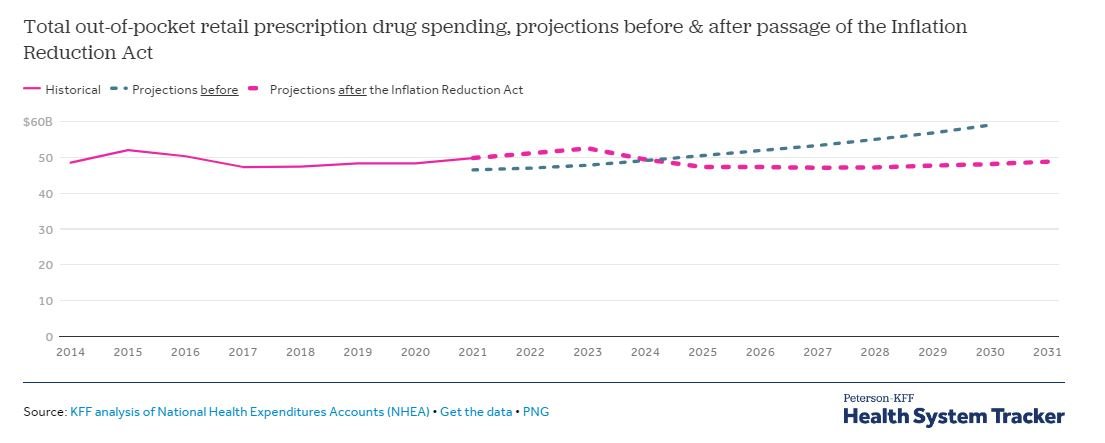

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 included numerous provisions aimed at prescription drug spending in the Medicare program, including capping insulin cost-sharing to $35 a month (starting 2023), requiring pharmaceutical manufacturers to pay rebates if prices exceed inflation (starting 2023), capping Medicare Part D out-of-pocket drug spending by eliminating the 5% coinsurance requirement for catastrophic coverage (in 2024) and adding a hard cap at $2,000 (starting in 2025) , and requiring the federal government to negotiate prices for some high-spend drugs (negotiated prices take effect in 2026). Before the Inflation Reduction Act, CMS projected aggregate out-of-pocket retail prescription drug spending to increase steadily throughout the 2020s. CMS now expects out-of-pocket drug spending to peak in 2023 at $52.5 billion and decline thereafter through 2027 as provisions take effect. By 2030, total out-of-pocket spending on retail prescription drugs is projected to be $48.1 billion, 18.5% lower than the $59.0 billion projected previously. While none of these provisions cover privately insured people, the effects of some of the Medicare drug price regulations may spill over to the private market, though the effects are highly uncertain, including whether manufacturers might attempt to make up for lost revenue in Medicare by raising prices for other payers.

What new policies might affect PBMs, the so-called prescription drug middlemen?

Many proposals have sought to increase transparency in pharmaceutical benefit manager (PBM) operations, for example, by requiring the disclosure of rebates and discounts negotiated with pharmaceutical manufacturers. Transparency measures are intended to provide more clarity on the pricing dynamics within the pharmaceutical supply chain. Other proposals are aimed at regulating how the PBM market operates; for example, banning PBMs from charging health plans more for a drug than the amount they reimburse pharmacies (a practice known as “spread pricing”), requiring PBMs to pass on all rebates received from manufacturers to health plans, or limiting compensation to PBMs based on a flat-dollar service fee, which would dampen current incentives around rebates based on high drug prices. Additional efforts have focused on market dynamics and competition among PBMs. For example, the Federal Trade Commission recently has deepened its inquiry into business practices of PBMs and rebate aggregators. These efforts may shed light on the impact of rebates and discounts on health care costs in the future. The House passed legislation in December 2023 with several provisions targeting PBMs, but it is unclear which provisions could become law as part of broader health care or spending-related legislation this year.